- Author: Ryan Singer

- URL: https://basecamp.com/shapeup

- long enough to build something meaningful and short enough that everyone feels the deadline looming from the start

- Done before its handed over to the team

- A small senior group works in parallel to the cycle teams to define key elements of a solution

- Concrete enough that the teams know what to do, yet abstract enough that they can work out the details

- Instead of asking how much time it will take to do some work, we ask: How much time do we want to spend? How much is this idea worth?

- Give full responsibility to team of designers and programmers to their own tasks, make adjustments to the scope, and work together to build vertical slices of the product one at a time

- Risk of not shipping on time, not risk of building the wrong things (Read the book: Competing against luck)

- Reduce risk by solving open questions before commiting to a project. Don't give something out that has gaping holes and tangled dependencies.

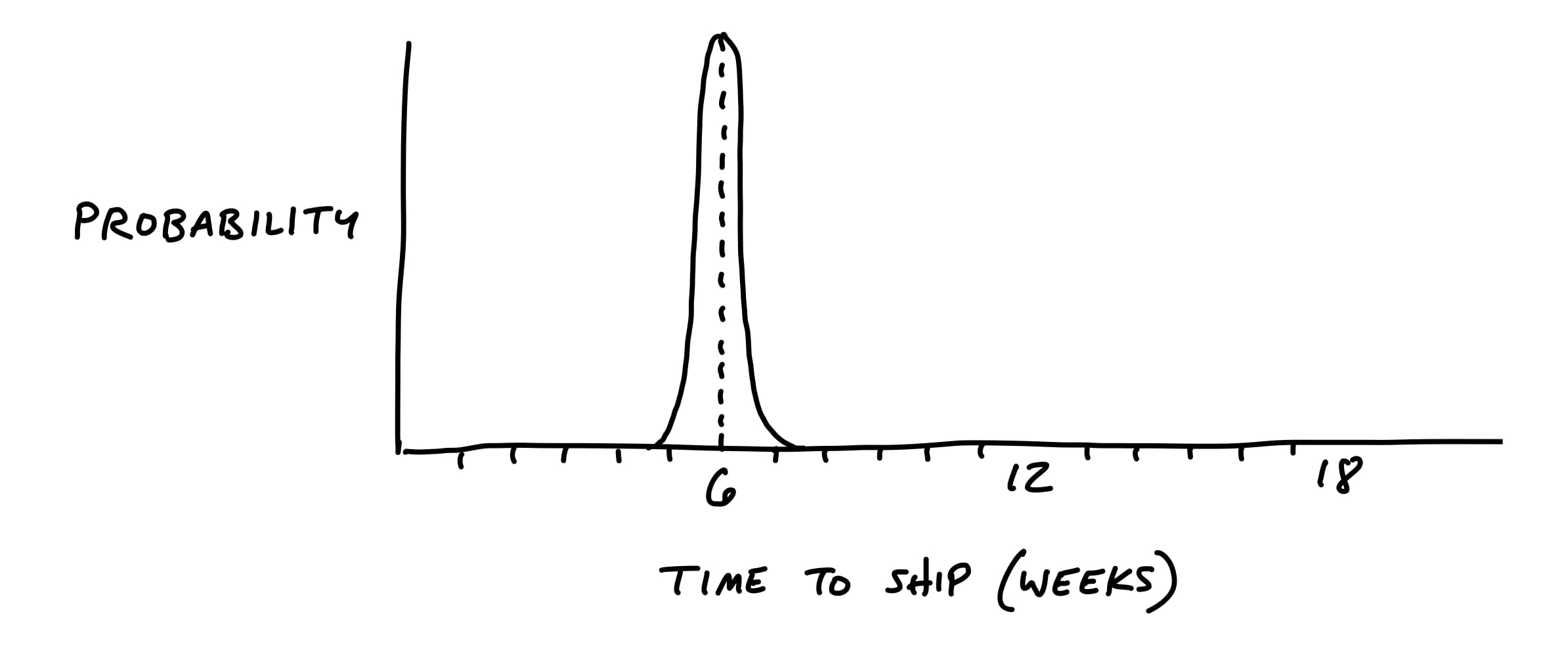

- If a project runs over 6 weeks, by default it doesn't get an extension.

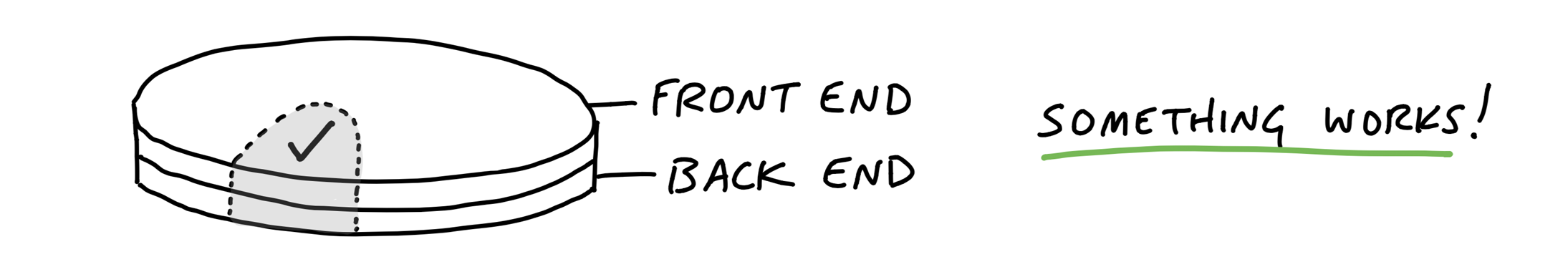

- Build one meaningful piece of the work end-to-end early on and then repeat

- Integrating as soon as possible, learn from feedback

- wireframes or high-fidelity mockups define too much detail too early, leaving designers no room for creativity.

-

"I know you're looking at this, but that's not what I want you to design. I want you to re-think it!" It's hard to do that when you're giving them this concrete thing. -

- @niazangels is guilty of the above :(

- Opposite side of the spectrum

-

"Perform a semantic search"

-

"Add notifications"

-

"Build a calendar view"

-

- Under-specified projects naturally grow out of control because there's no boundary to define what's out of scope.

Past versions of Basecamp had calendars, and only about 10% of customers used them. That's why we didn't have the appetite for spending six months on a calendar. On the other hand, if we could do something to satisfy those customers who were writing us in one six week cycle, we were open to doing that.

With only six weeks to work with, we could only build about a tenth of what people think of when they say "calendar." The question became: which tenth?

-

It's rough

- Everybody knows its unfinished

- Leave room for designers and programmers to assess trade offs, apply their judgement

-

It's solved

- clear direction showing what to do, even if its rough

- no known holes

-

It's bounded

- clearly indicates what not to do

- fixed amount of time requires limiting the scope and leaving specific things out

- Inferface + Technology for solving Business problems

- Shaping is primarily design work

- Questions:

- What are we trying to solve?

- Why does it matter?

- What counts as success?

- Which customers are affected?

- What is the cost of doing this instead of something else?

- Closed door activity - private, rough, early work.

- Move fast, speak frankly and jump from one promising position to another

- No one outside the room should be able interpret

- Unshaped work is risky. So keep two separate tasks:

- Shaping

- shapers are working on what the teams might potentially build in a future cycle

- Building

- building work that's been previously shaped

- Shaping

Work on the shaping track is kept private and not shared with the wider team until the commitment has been made to bet on it. That gives the shapers the option to put work-in-progress on the shelf or drop it when it's not working out.

- Set boundaries

- define the problem

- assess how much time the idea is worth

- Rough out the elements

- abstract sketches

- output is an idea that solves the problem within time, finer details are left out

- Address risks

- find holes, unanswered questions

- amend solution, cut out scope

- prevent team from getting stuck

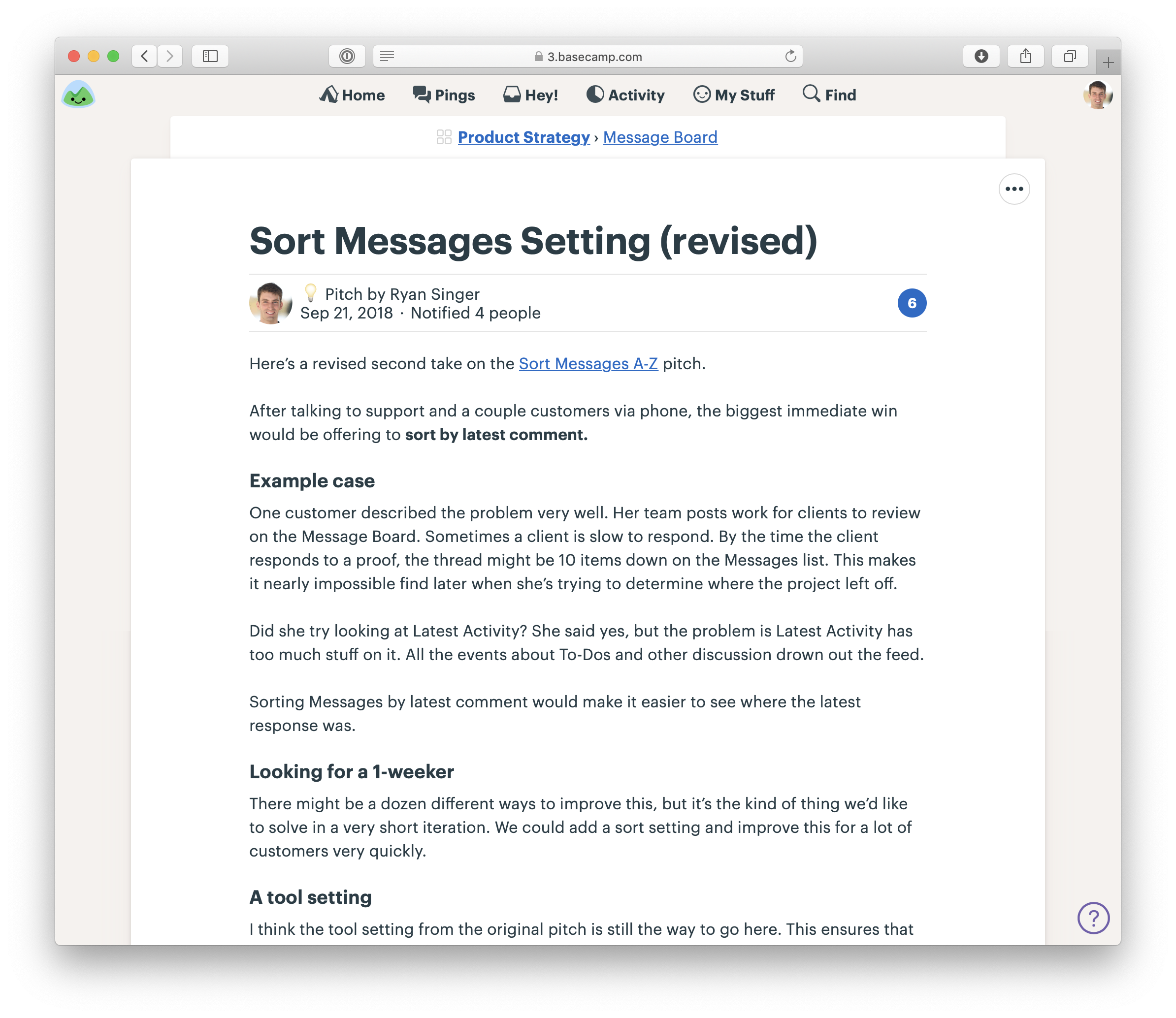

- Write pitch

- package it with a formal write-up called a pitch.

- The pitch summarizes the problem, constraints, solution, rabbit holes, and limitations.

- The pitch goes to the betting table for consideration.

- A raw idea is an unshaped idea. eg. "customers are asking for group notifications"

Sometimes an idea gets us excited right away. In that case we need to temper the excitement by checking whether this is really something we're going to be able to invest time in or not.

If we don't stop to think about how valuable the idea is, we can all jump too quickly to either committing resources or having long discussions about potential solutions that go nowhere.

- Apetite is set in 2 batches:

-

Small Batch: This is a project that a team of one designer and one or two programmers can build in one or two weeks. We batch these together into a six week cycle (more on that later).

-

Big Batch: This project takes the same-size team a full six-weeks.

-

When you have a deadline, all of a sudden you have to make decisions. With one week left, I can choose between fixing typos or adding a new section to a chapter.

- Without a time limit, there's always a better version

- The amount of time we set for our appetite is going to lead us to different solutions

- We can only judge what is a "good" solution in the context of how much time we want to spend and how important it is.

- Default response should be a very soft "no" that leaves all our options open. We don't put it in a backlog.

- It's too early to say "yes" or "no" on first contact. Even if we're excited about it.

- We don't want to shut down an idea that we don't understand. New information might come in tomorrow that makes us see it differently.

- Showing too much enthusiasm right away can set expectations that this thing is going to happen.

- @niazangels - Step 3 infinite scroll idea from client

We once had a customer ask us for more complex permission rules. It could easily have taken six weeks to build the change she wanted. Instead of taking the request at face value, we dug deeper.

It turned out that someone had archived a file without knowing the file would disappear for everyone else using the system.

Instead of creating a rule to prevent some people from archiving, we realized we could put a warning on the archive action itself that explains the impact. That's a one-day change instead of a six-week project.

- Ask "why they want it" and "when did they wish for it". Discover the underlying reason to cut scope and prevent working on the wrong things

- Compare against baseline: A baseline is what customers are doing without the thing they're asking for.

- If it's not critical, or problem is unclear, walk away from it. Maybe a future request will give us more insight.

- worst requests are "redesigns" or "refactorings" that aren't driven by a single problem or use case

- "redesign the Files section," is a grab-bag, not a project.

- a more productive starting point: "We need to rethink the Files section because sharing multiple files takes too many steps." Now we can start asking questions.

- If you have the following, you have enough to start building solutions

- A raw idea

- An appetite

- A narrow problem definition

- There could be dozens of different ways to approach the solution for a problem. It's important to move fast and cover a lot of different ideas without getting dragged down.

-

First, we need to have the right people—or nobody—in the room. Either we're working alone or with a trusted partner who can keep pace with us.

-

Second, we need to avoid the wrong level of detail in the drawings and sketches

-

Key questions to ask yourself:

- Where in the current system does the new thing fit?

- How do you get to it?

- What are the key components or interactions?

- Where does it take you?

-

To keep away from touching finer details: Use breadboarding and fat marker sketches

-

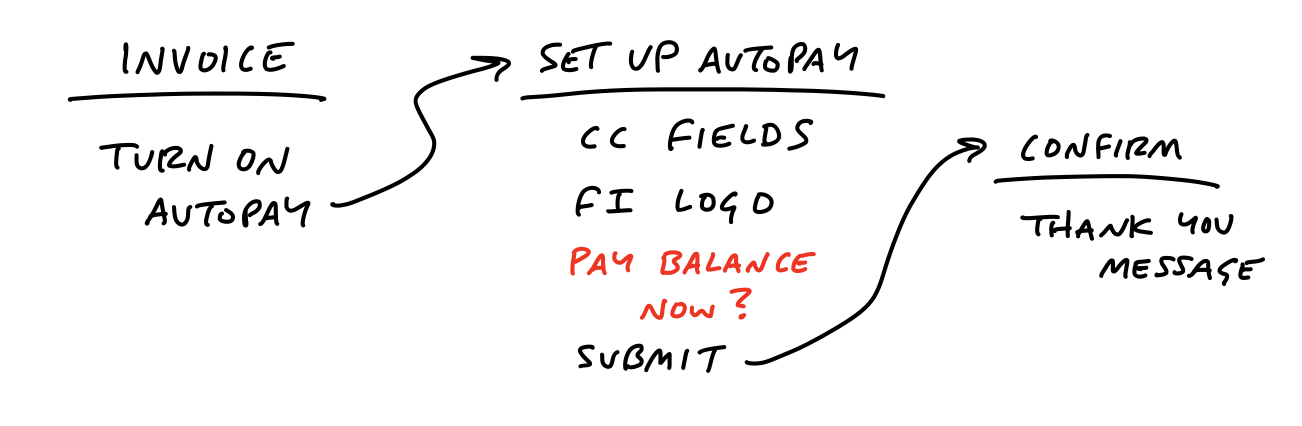

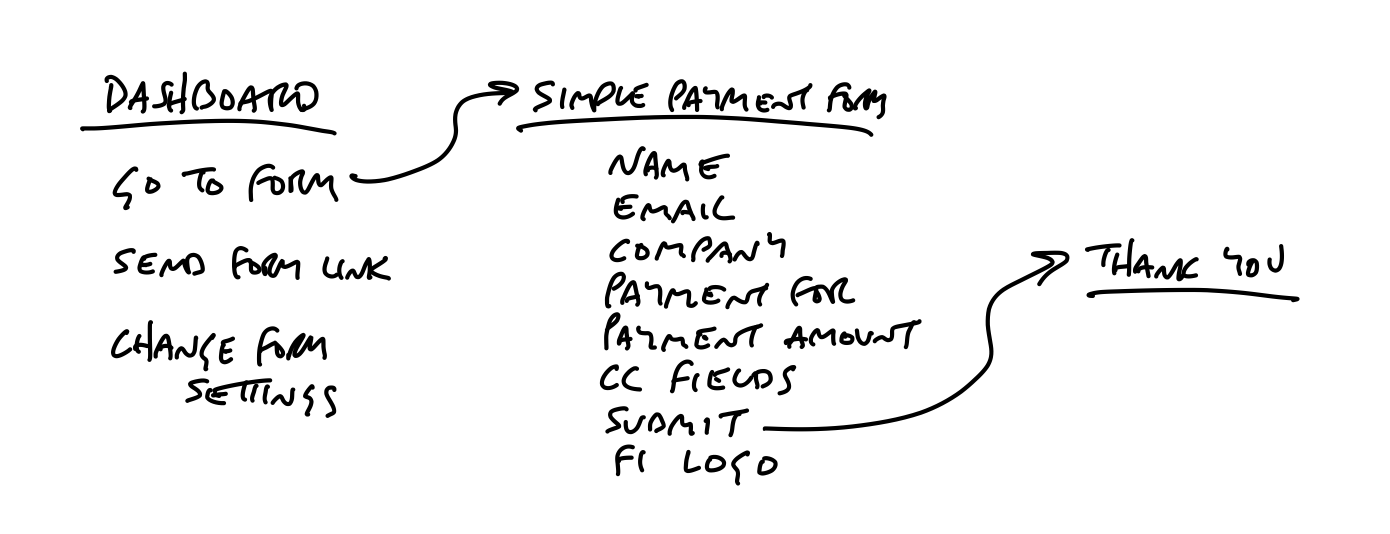

There are three basic things to draw:

- Places : These are things you can navigate to, like screens, dialogs, or menus that pop up.

- Affordances : These are things the user can act on, like buttons and fields. We consider interface copy to be an affordance, too. Reading it is an act that gives the user information for subsequent actions.

- Connection lines: These show how affordances from place to place.

-

Question: Did we actually pay the original invoice or not? Now we have both functional and interface questions. And where do we explain this behavior? We could add an option to the Setup screen

-

But now we're complicating the responsibilities of the confirmation screen. We're going to need to show a receipt if you pay your balance now. Should the confirmation have a condition to sometimes show a receipt of the amount just paid?

-

How about an entirely different approach. Instead of starting on an Invoice, we make Autopay an option when making a payment. This way there's no ambiguity about whether the current amount is being paid.

-

What about after Autopay is enabled? How does the customer turn it off? Up to this point, many customers in the system didn't have usernames or passwords. They followed tokenized links to pay the invoices one by one.

-

The team in this case decided that adding the username/password flows was too much scope for their appetite at the time.

-

We could add a single option to disable Autopay in the customer detail page that we already offered to invoicers. (like unsubscribe in newsletters)

-

Illustrates the level of thinking and the speed of movement to aim for during the breadboarding phase

-

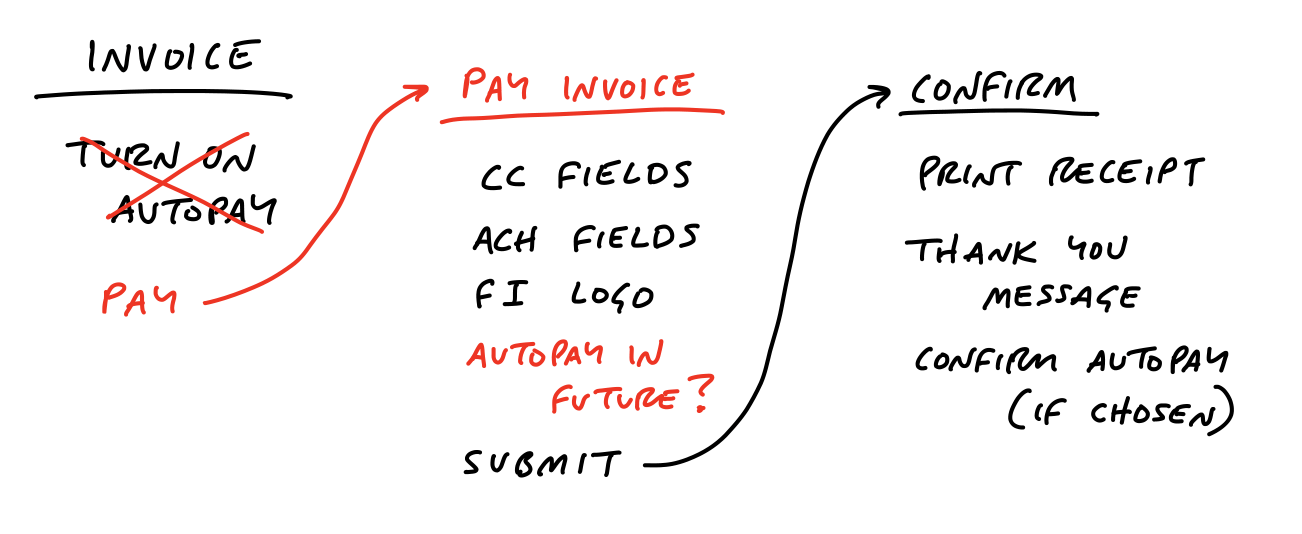

Sometimes the idea we have in mind is a visual one. Breadboarding would just miss the point because the 2D arrangement of elements is the fundamental problem.

-

Pen size set to a large diameter.

-

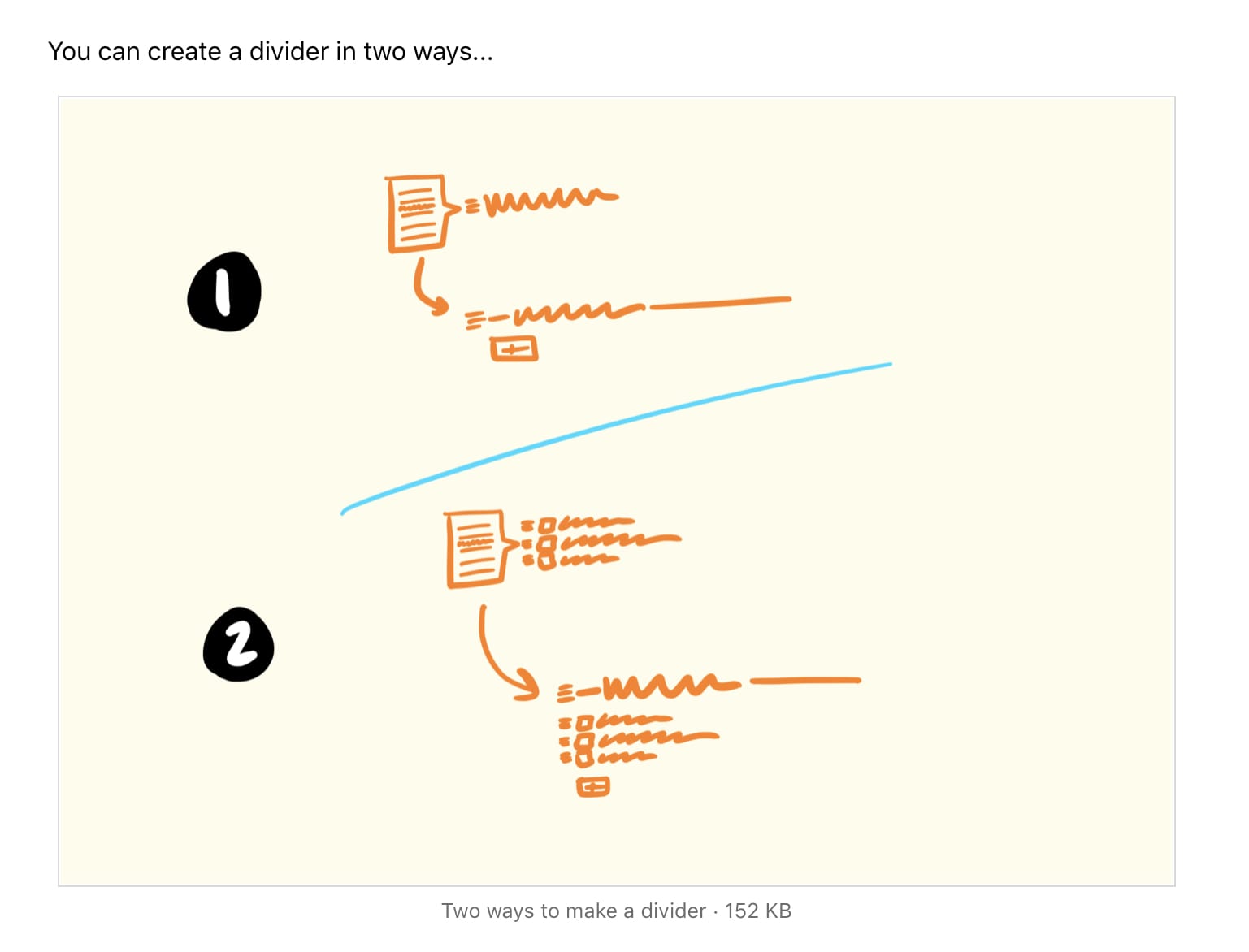

Were afraid it might break the flow of the lists

-

Autopay

- A new "use this to Autopay?" checkbox on the existing "Pay an invoice" screen

- A "disable Autopay" option on the invoicer's side

-

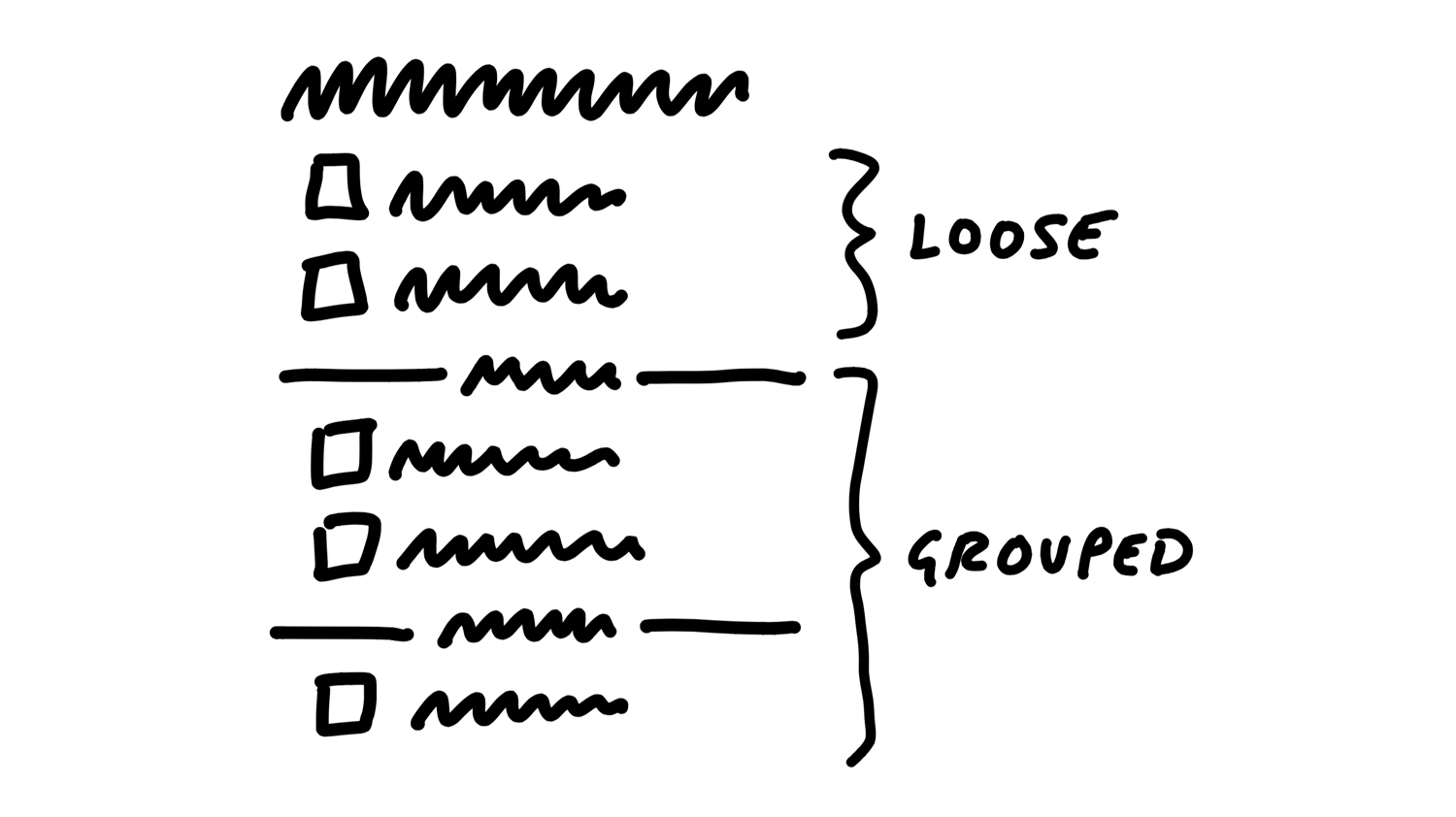

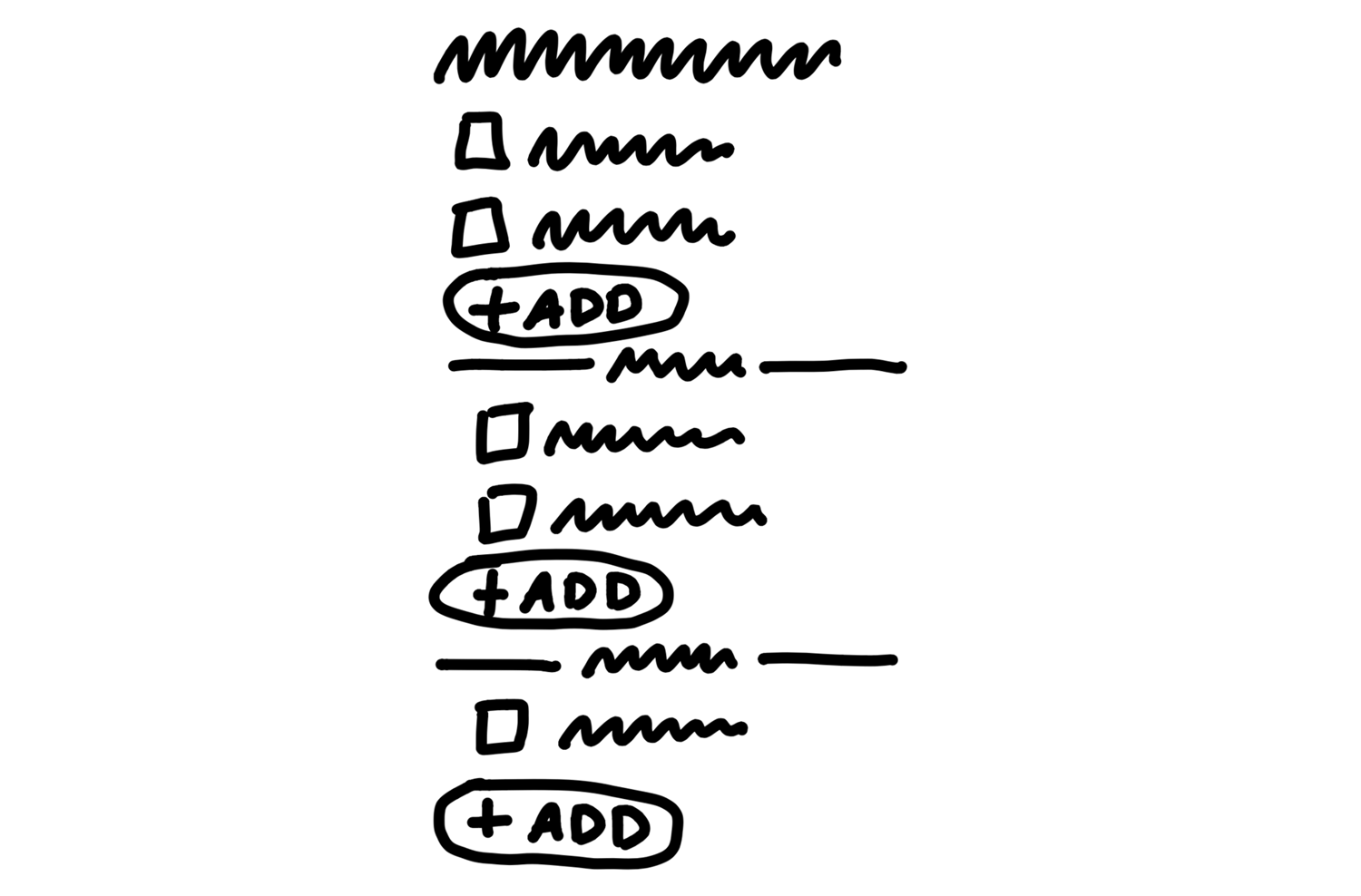

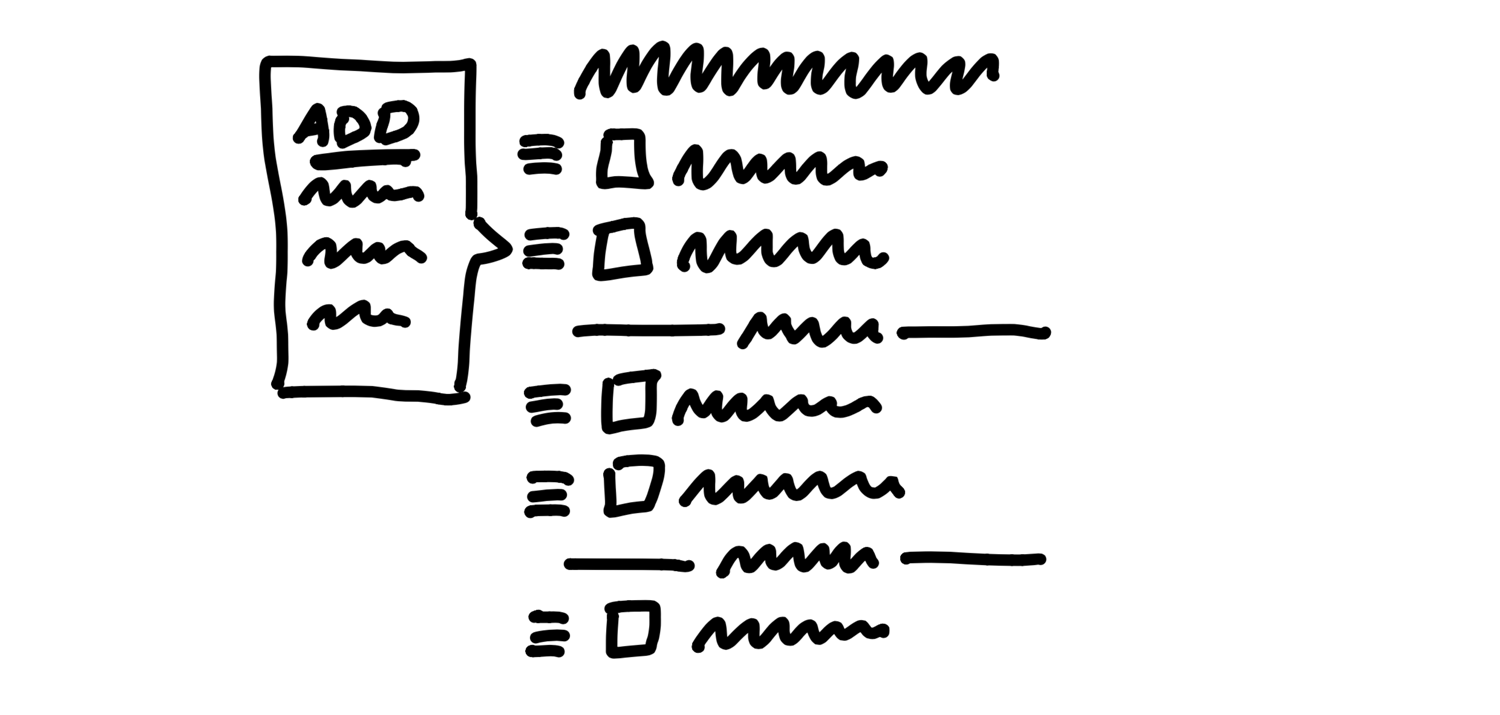

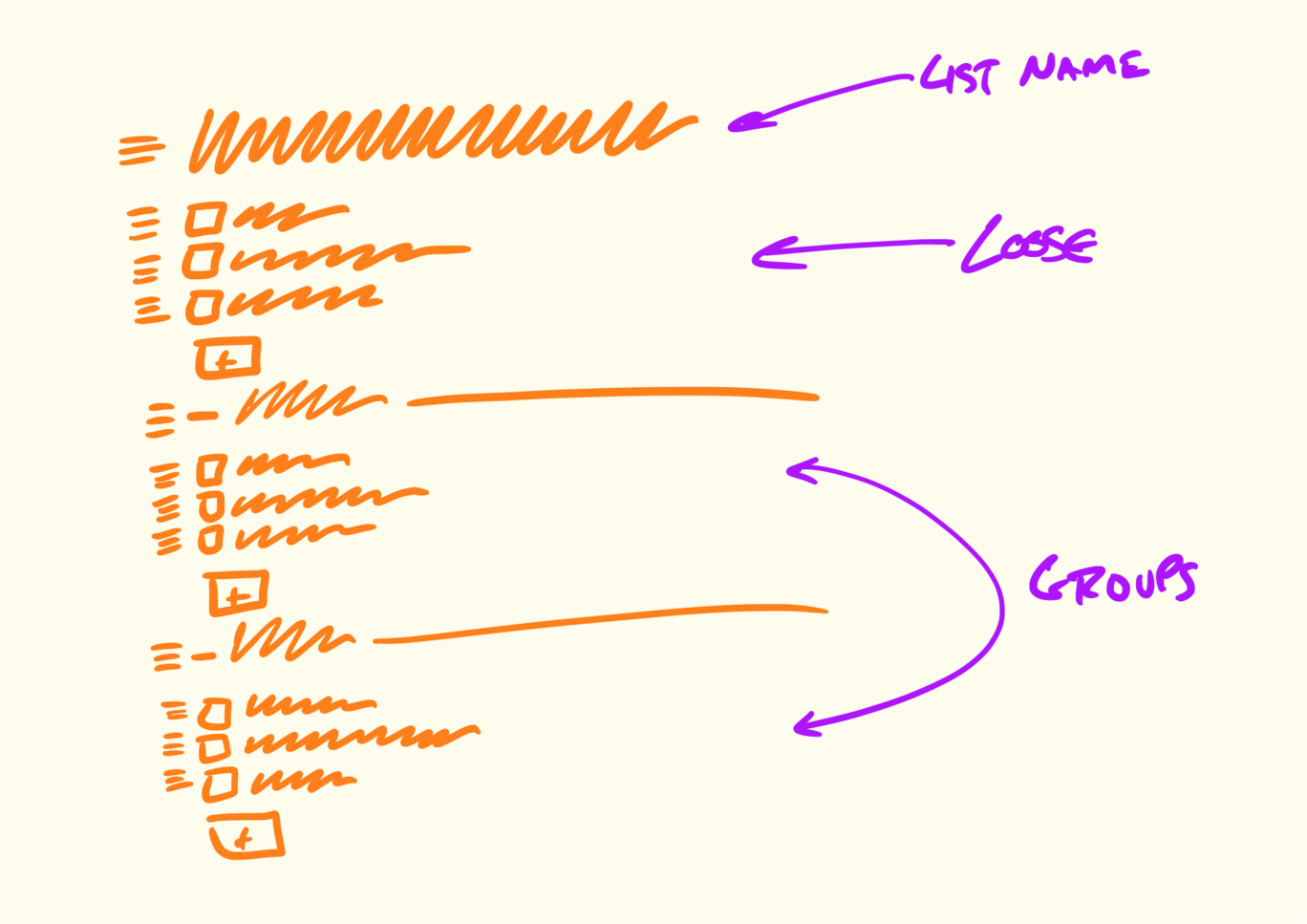

Todo

- Loose to-dos above the first group belong directly to the parent

- Grouped to-dos appear below the loose to-dos

- We'd like to try an add affordance within each section, but if that doesn't work visually, we're ok with relying on the action menu for inserting to-dos into position.

-

@niazangels: Multiple solutions are acceptable at this stage

-

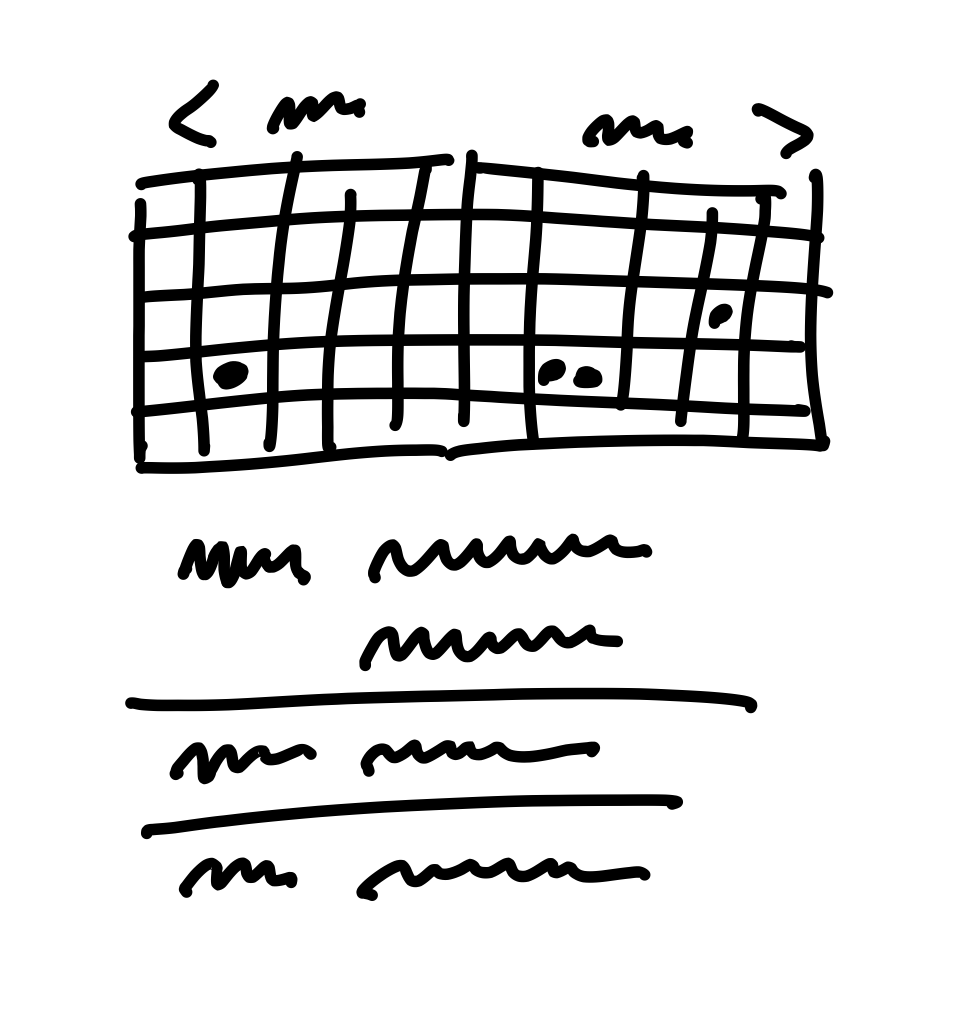

- A 2-up monthly calendar grid

- Dots for events, no spanned pills

- Agenda-style list of events below that scrolls an event into view when you tap a dot

-

This list of elements is extremely narrow and specific compared to "monthly calendar".

- You don't want to have to say "I know I drew it like this but ignore that…"

-

It's normal for the artifacts at this point to be indecipherable to anybody who wasn't there with you.

-

We’ve gone from a cloudy idea, like “autopay” or “to-do groups,” to a specific approach and a handful of concrete elements. But the form we have is still very rough and mostly in outline.

-

The next step is to do some stress-testing and de-risking. Then we wrap up with a pitch,

- At this stage, we could walk away from the project. We haven’t bet on it.

- We added value to the raw idea by making it more actionable.

-

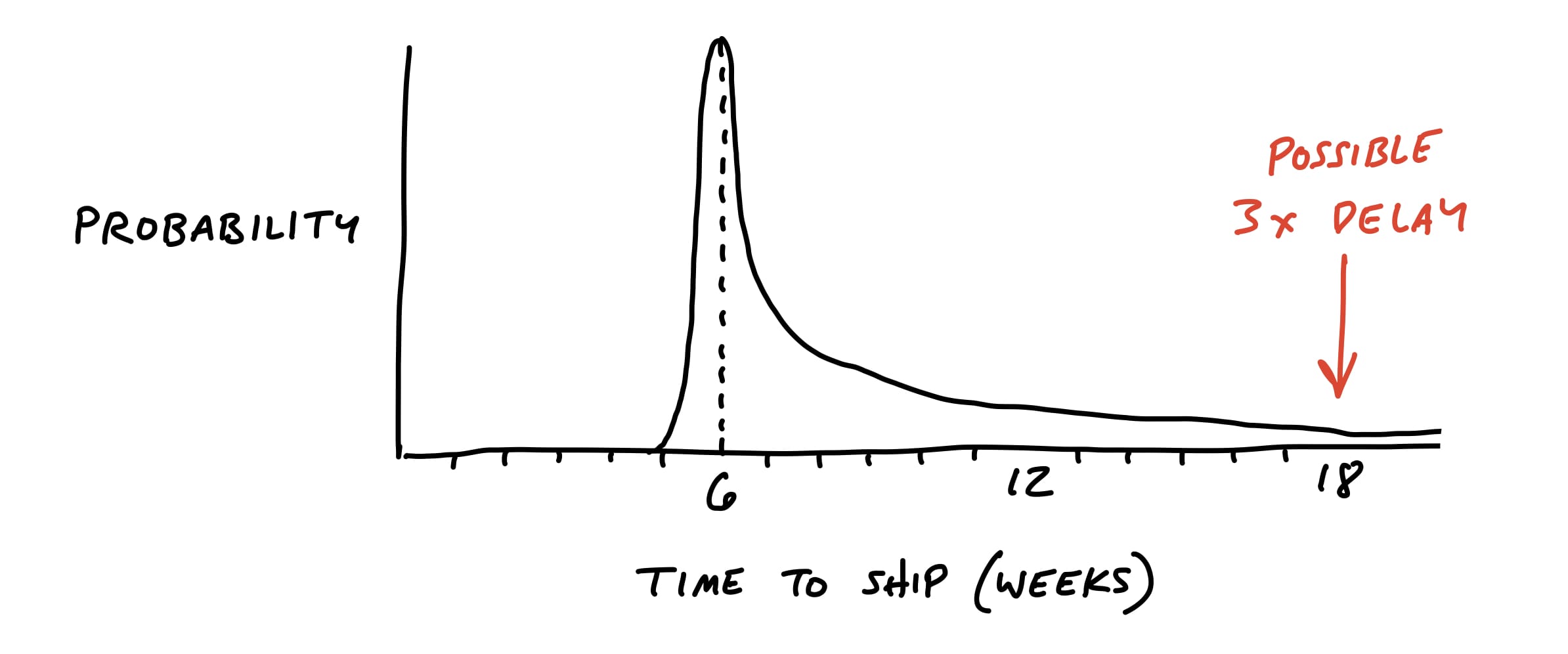

Shaped up work could be derailed off the 6 week timeline if there is even one major hole

-

There will always be unknowns, as is tackled in part 3.

-

Fleshing out the elements of the solution was a fast-moving, exploratory process. It was more breadth than depth

-

Did we miss anything? Are we making technical assumptions that aren't fair?

-

Questions to consider

- Does this require new technical work we've never done before?

- Are we making assumptions about how the parts fit together?

- Are we assuming a design solution exists that we couldn't come up with ourselves?

- Is there a hard decision we should settle in advance so it doesn't trip up the team?

-

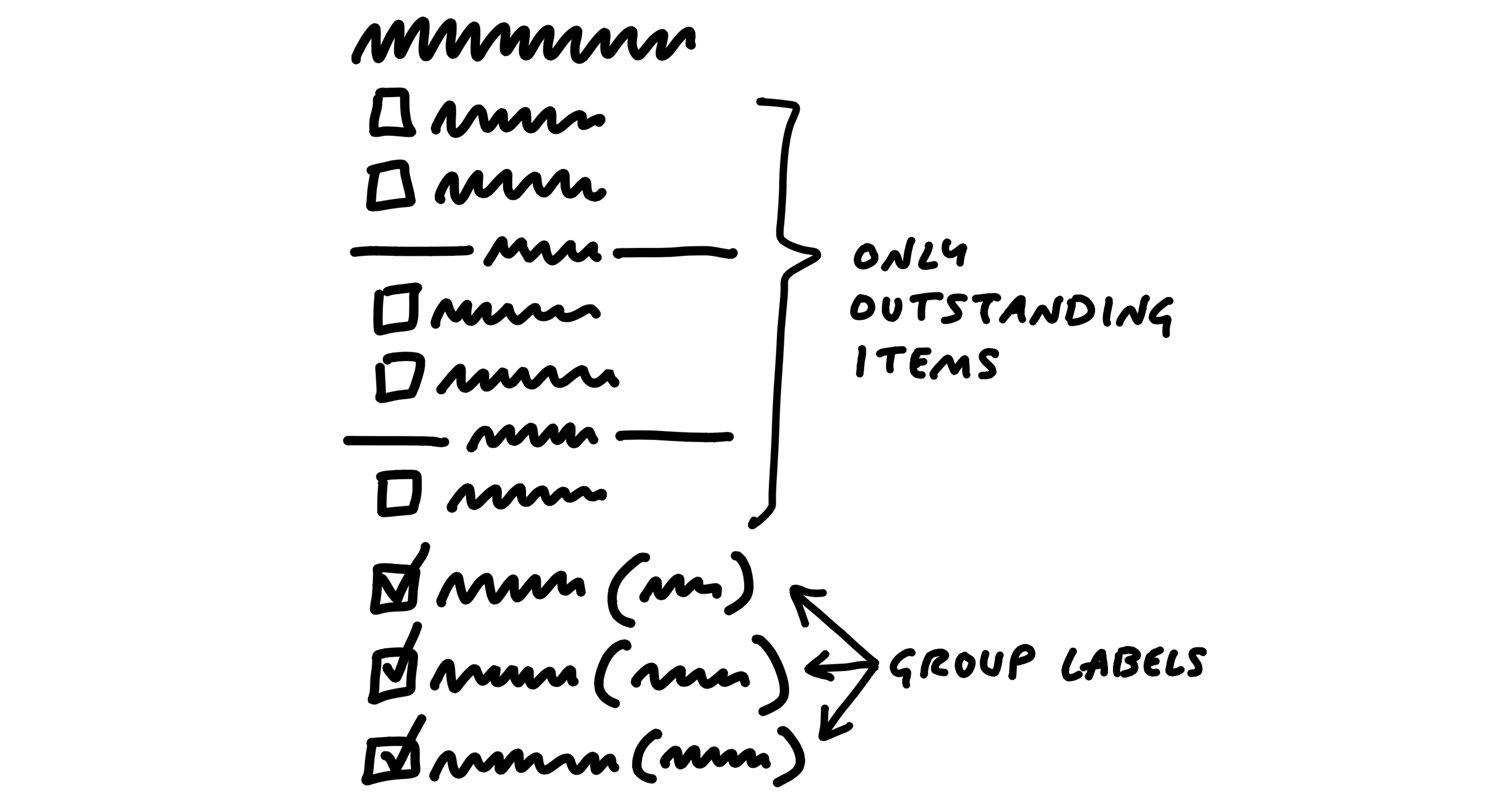

In the case of todo lists, what happens to the completed items?

- In the pre-existing design, the latest few completed items displayed below the list.

- Should we now render completed items at the bottom of each group instead of the list?

- Or should we continue to show completed items at the bottom, and repeat the same set of dividers within the completed items section?

- Should we reconsider how we handle completed items entirely?

-

If we didn’t address it, we’d be pushing a deep design problem down to the team and unreasonably asking them to find a solution under deadline.

-

We would leave the completed items exactly as they worked previously. Instead of grouping or segmenting them, we would just append the name of the group to each completed item.

-

When writing the pitch point out this specific “patch” as part of the concept, so nobody down the line will get tripped up on it.

-

@niazangels: I would never go for that solution!

- Team mates will of course look for all the use cases to cover and consider them necessary.

- Scope hammering: Forcefully questioning a design, implementation, or use case to cut scope and finish inside the fixed time box.

- Explicitly mark off the other cases as “out of bounds” for the project and focus on the win we want

- There may be parts of the solution we got excited about during the sketching phase that aren’t really necessary.

- Mention the nice-to-haves, but everyone should start from the assumption that the feature is valuable without it.

- Communicate that this is just an idea. It’s something you’re shaping as a potential bet

- “Here’s something I’m thinking about… but I’m not ready to show anybody yet… what do you think?”

- In software, everything is possible but nothing is free.

- Instead of asking “is it possible to do X?” ask “is X possible in 6-weeks?” That’s a very different question.

- You’re looking for risks that could blow up the project.

- Rather than writing up a document or creating a slideshow, invite them to a whiteboard and redraw the elements as you worked them out earlier, building up the concept from the beginning

- open it up and invite them to suggest revisions.

-

we have the elements of the solution, patches for potential rabbit holes, and fences around areas we’ve declared out of bounds.

-

Betting table: A meeting during cooldown when stakeholders decide what bets to make

-

we write it up in a form that communicates the boundaries and spells out the solution so that people with less context will be able to understand and evaluate it

-

This pitch will be the document that we use to

- lobby for resources,

- collect wider feedback if necessary

- capture the idea for when the time is more ripe

-

The purpose of the pitch is to present a good potential bet.

-

Put the concept into a form that other people will be able to understand, digest, and respond to.

-

There are five ingredients that we always want to include in a pitch:

- Problem — The raw idea, a use case, or something we’ve seen that motivates us to work on this

- Appetite — How much time we want to spend and how that constrains the solution

- Solution — The core elements we came up with, presented in a form that’s easy for people to immediately understand

- Rabbit holes — Details about the solution worth calling out to avoid problems

- No-gos — Anything specifically excluded from the concept: functionality or use cases we intentionally aren’t covering to fit the appetite or make the problem tractable

-

Always present a problem and a solution together.

-

Without a specific problem, there’s no test of fitness to judge whether one solution is better than the other.

-

The best problem definition consists of a single specific story that shows why the status quo doesn’t work.

-

What if the problem only happens to customers who are known to be a poor fit to the product? We could spend six weeks that only benefits a small percentage of customers known to have low retention.

-

Six weeks, not three months, or—in the case of a small batch project—two weeks, not the whole six weeks.

-

Stating the appetite in the pitch prevents unproductive conversations. There’s always a better solution given infinite time.

-

Problems with no shaped up solution is not ready to be bet upon and should be avoided

-

Giving it to a team means pushing research and exploration down to the wrong level where resources are limited

-

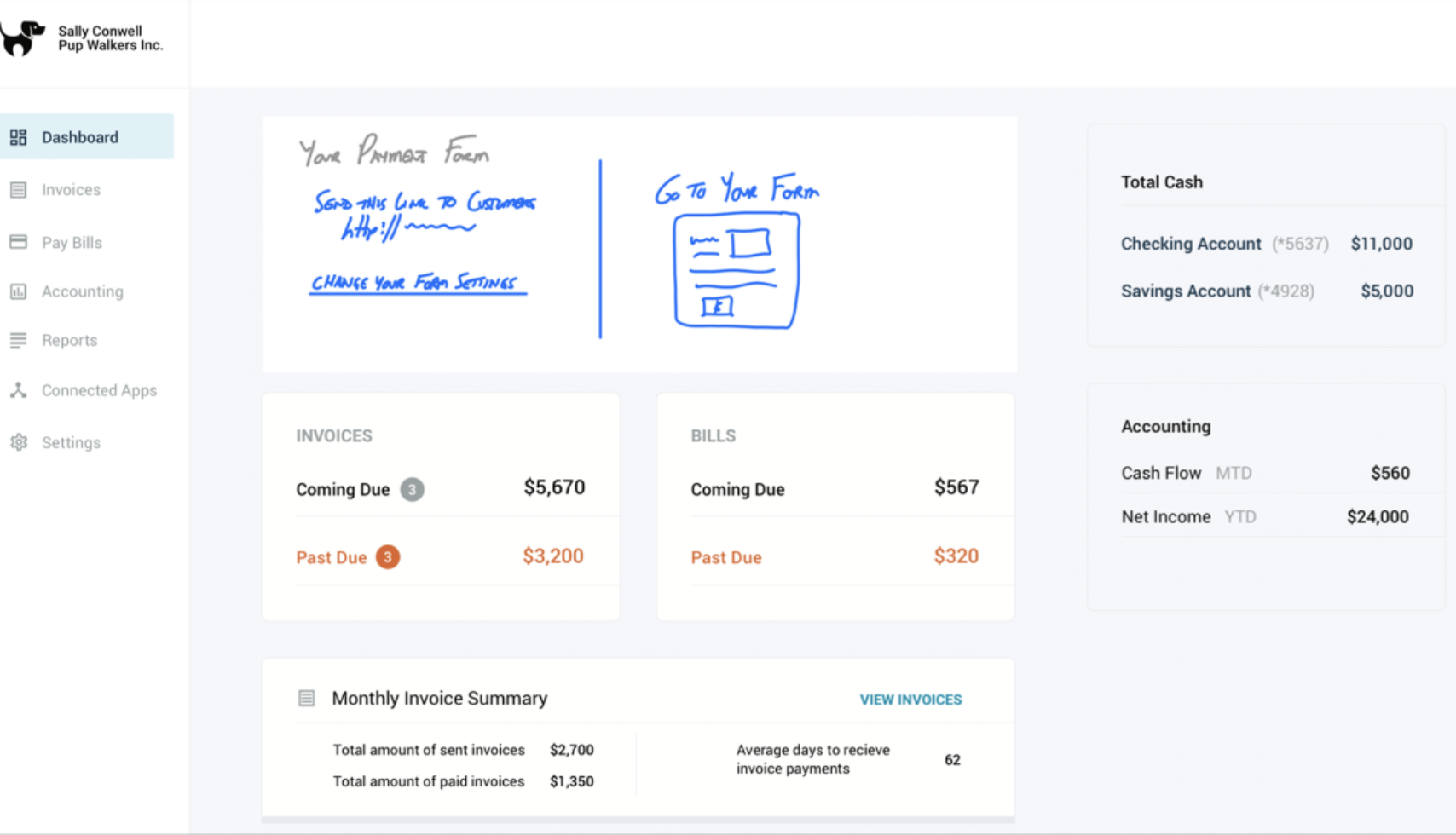

Slow down and prepare a proper presentation. Stay high level, but add a little more concreteness than in the finding elements phase.

-

Don’t over-specify the design. They’ll box in the designers who do the work later.

-

The downside is we’ve gotten into some layout decisions that would have been nice to avoid.

-

selectively get into more visual detail because we need it to sell the concept.

- Usually just requires a few lines of text.

- Anything we’re not doing in this concept

- eg. Decide up front that they wouldn’t allow any kind of WYSIWYG editing of the form.

- WYSIWYG might be better in some peoples’ eyes, but given the appetite it was important to mark this as a no-go.

- Async communication by default and escalate to real-time only when necessary

- This gives everyone the maximum amount of time under their own control for doing real work, keeps the betting table short and productive

- People comment on the pitch asynchronously. Not to say yes or no — that happens at the betting table — but to poke holes or contribute missing information.

- Backlogs are a big weight we don’t need to carry.

- tasks pile up that we all know we’ll never have time for

- growing pile gives us a feeling like we’re always behind even though we’re not

- Just because somebody thought some idea was important a quarter ago doesn’t mean we need to keep looking at it again and again.

- Big time wasters too. Time is spent constantly reviewing, grooming and organizing old ideas.

-

Before each six-week cycle, we hold a betting table where stakeholders decide what to do in the next cycle.

-

At the betting table, they look at pitches from the last six weeks — or any pitches that somebody purposefully revived and lobbied for again.

-

Nothing else is on the table. No backlog issues.

-

If we decide to bet on a pitch, it goes into the next cycle to build. If we don’t, we let it go. There’s nothing we need to track or hold on to.

-

What if the pitch was great, but the time just wasn’t right? Anyone who wants to advocate for it lobbies for it six weeks later.

-

Everyone can still track pitches, bugs, requests, or things they want to do independently without a central backlog.

-

Support can keep a list of requests or issues that come up more often than others. Product tracks ideas they hope to be able to shape in a future cycle. Programmers maintain a list of bugs they’d like to fix when they have some time. There’s no one backlog or central list and none of these lists are direct inputs to the betting process.

-

Regular but infrequent one-on-ones between departments help to cross-pollinate ideas for what to do next. Support can tell Product about top issues- which Product may shape up

-

People from different departments can advocate for whatever they think is important and use whatever method works for them to track those things

-

This way the conversation is always fresh. Anything brought back is brought back with a context, by a person, with a purpose. Everything is relevant, timely, and of the moment.

- Ideas are cheap. They come up all the time and accumulate into big piles. Really important ideas will come back to you

- A bug that customers are running into from time to time—it’ll come back to your attention when a customer complains again or a new customer hits it.

- @niazangels Step 3 "Accept all", "Accept" from Step 2.

- Need to know who is available and for how long in case of overlapping projects

- A cycle gives us a standard project size both for shaping and scheduling.

- Two weeks is too short to get anything meaningful done and have high planning overhead.

- Cycles need to be long enough to do meaningful work but short enough to ensure that people feel the deadline looming from the start

- Six week cycle + 2 week cool down

- Need time to breathe and think about what’s next

- The end of a cycle is the worst time to meet and plan because everybody is too busy finishing projects and making last-minute decisions in order to ship on time.

- During cool-down, programmers and designers on project teams are free to work on whatever they want.They use it to fix bugs, explore new ideas, or try out new technical possibilities.

- 1 designer + 2 programmers

- 1 QA does the integration testing later

- Teams will either spend:

- entire cycle working on one project (big batch)

- work on multiple smaller projects during the cycle (small batch)

- Small batch projects run one or two weeks, and are decided by the team how they can be scheduled

- Output of the call is a cycle plan.

- CEO, CTO, a senior programmer, and a product strategist

- the call rarely goes longer than an hour or two

- There’s no “step two” to validate the plan or get approval. And nobody else can jump in afterward to interfere or interrupt the scheduled work.

- meeting is short, the options well-shaped, and the headcount low.

- “betting”, instead of planning, sets different expectations.

- First, bets have a payout. We’re not just filling a time box with tasks until it’s full.

- Second, bets are commitments.: we commit to giving the team the entire six weeks to work exclusively on that thing with no interruptions.

- Third, a smart bet has a cap on the downside. If we bet six weeks on something, the most we can lose is six weeks.

- @niazangels:

diffsfeature would have been better to be time boxed and discarded if we had made a bet for 2 weeks

- It’s not really a bet if we say we’re dedicating six weeks but then allow a team to get pulled away to work on something else. When you make a bet, you honor it.

- When you pull someone away for one day to fix a bug or help a different team, you don’t just lose a day. You lose the momentum they built up and the time it will take to gain it back.

- What if something comes up during that six weeks? The maximum time we’d have to wait is six weeks. Do not interrupt the team.

- It’s very important to only bet one cycle ahead. This keeps our options open to respond to these new issues.

- If it’s a real crisis, we can always hit the brakes. But true crises are very rare.

- We combine this uninterrupted time with a tough but extremely powerful policy.

- Teams have to ship the work within the amount of time that we bet. If they don’t finish, by default the project doesn’t get an extension.

- First, it eliminates the risk of runaway projects. If it was allowed 6 weeks, we prevent it from taking 2x-3x that time.

- Second, if a project doesn’t finish, it means we did something wrong in the shaping. Instead of investing more time in a bad approach, the circuit breaker pushes us to reframe the problem.

- .Circuit breaker thus ensures one project doesn’t overload the system.

- Finally, the circuit breaker motivates teams to take more ownership including making trade-offs about implementation

- A hard deadline and the chance of not shipping motivates the team to regularly question their design and implementation wrt. scope

- Nothing special about bugs that makes them automatically more important than everything else.

- If we’re in a real crisis, we’ll drop everything to fix it. But crises are rare.

- If we tried to eliminate every bug, we’d never be done.

- You can’t ship anything new if you have to fix the whole world first.

- @niazangels - Mega Issues are forever open problems about the world

- Three recommended strategies

- Use cool-down: two weeks every six weeks actually adds up to a lot of time for fixing them.

- Bring it to the betting table: If a bug is too big to fix during cool-down, it can compete for resources at the betting table. eg. synchronous step to an asynchronous job

- Schedule a bug smash: Once a year—usually around the holidays—we’ll dedicate a whole cycle to fixing bugs. Hard to get normal work done when people are taking their days off.The team can self-organize to pick off the most important bugs.

- The key to managing capacity is giving ourselves a clean slate with every cycle.

- We don’t know what brilliant idea will emerge or what urgent request might appear.

- Suppose we envision a feature that takes two cycles to ship. We reduce our risk dramatically by shaping a specific six week target, with something fully built and working at the end of that six weeks. If that goes as expected, we’ll feel good about betting the next six weeks the way we envisioned in our heads. But if it doesn’t, we could define a very different project.

- Three phases generally

- The way that we shape and our expectations for how the team works during the cycle are different.

- These phases unfold over the course of multiple cycles, but we still only bet one cycle at a time.

-

our idea is just a theory or a glimmer

-

don’t know if the bundle of features we imagine will hold together in reality

-

there is a lot of scrapwork. We might decide half-way to standing up a feature that it’s not what we want and try another approach instead.

-

In other words, we can’t reliably shape what we want in advance and say: “This is what we want. We expect to ship it after six weeks.”

-

Adjustments for this phase

- The shaping is much fuzzier because we expect to learn by building.

- Senior people make up the team because

- You can’t delegate to other people when you don’t know what you want yourself.

- Architectural decisions will determine what’s possible in the product’s future

- Lastly, we don’t expect to ship anything at the end of an R&D cycle. The aim is to spike, not to ship.The goal is to learn what works so we can commit to some load-bearing structure: frontend and backend.

- Best case scenario: some UI and code committed to serve as the foundation

-

We can’t ship anything to customers with just a single cycle of R&D work. But we still don’t commit to more than one cycle at a time. We may learn from the first cycle that we aren’t ready to tackle the product yet.

- The key architectural decisions are settled. The product does those few essential things that define it, and the foundation is laid for the rest.

- Now we behave exactly the same as when we work on an existing product. Regular shape up process

- Adjustments:

- Shaping is deliberate again.

- No longer limited to the senior group.

- Shipping is the goal, not spiking. Shipping means merging into the main codebase.

- Since we aren’t shipping to customers at the end of each cycle, we maintain the option to remove features from the final cut before launch.

- We can bet six weeks on a feature without knowing if we’ll want it in the final product. That’s not a problem as long as we set expectations for the build team: we can’t predict what we’ll want in the final cut, and we’re willing to risk this cycle to take our best swing at the idea.

-

In the final phase before launching the new product, we throw all structure out the window. 🤣

-

Clean up: Unstructured and unshaped part before launch to fix whatever is needed

-

Things we dismissed before pop out at us with new importance - bugs, things we forgot, things we missed.

- There’s no shaping

- Leadership stands at the helm throughout the cycle, calling attention to what’s important

- Work is merged to the main codebase continuously in as small bites as possible.

- We have to check ourselves to make sure these are must-haves we’re working on, not just our cold feet begging us to delay launch. Cleanup shouldn’t last longer than two cycles.

-

Sometimes we need to see all the features working as a whole to judge what we can live without and what might require deeper consideration

-

@niazangels - Sprint 1 launch of Voody, we never had the whole picture until the last day.

- HEY was in R&D mode for the first year of its development

- Jason (CEO), David (CTO), and Jonas (senior designer) explored a wide variety of ideas before settling on the core.

- Nearly a year of production mode cycles followed, where the whole team fleshed out HEY’s feature set.

- We ended with two cyles of cleanup and significantly cut back the feature set to launch in July 2020.

- The betting table didn’t know they would be working on HEY for two years during those first few R&D cycles.

- Break into multiple cycles- first cycle should delivers somethings useful but need not be shipped to customers.

- Don't expect to ship it to customers without doing an additional cycle on it.

-

Does the problem matter?

- The solution doesn’t matter if the problem isn’t worth solving.

- Of course, any problem that affects customers matters. But we have to make choices because there will always be more problems than time to solve them.

- Sometimes a solution that is too complicated or too sweeping may invite questions about the problem.

- Narrow down to get 80% of the benefit from 20% of the change.

-

Is the appetite right?

- Suppose a stakeholder says they aren’t interested in spending six weeks on a given pitch

- Maybe the problem wasn’t articulated well enough, and there’s knowledge that the shaper can add to the conversation right now to swing opinion.

- “Yeah it doesn’t happen often, but when it does people are so vocal about it that it really tarnishes perception of us.”

- “Maybe it sounds trivial, but support has to go through 11 time-consuming steps to get to resolution.”

- Sometimes saying “no” to the time commitment is really saying no to something else. To uncover, ask:

- “How would you feel if we could do it in two weeks?”

- CTO might answer: “I don’t want to introduce another dependency into that area of the app.”

- The shaper might just let the idea go if interest is too low.

- The shaper might go back to the drawing table and either work on a smaller version (for a shorter appetite) or do more research if they believe the problem is compelling but they weren’t armed well enough to present it.

-

Is the solution attractive?

- problem may be important and the appetite fair, but there can be differences about the solution.

- Eg. if the solution involves adding a button, we give up real estate which can't be used in the future.

- Someone might offer an immediate design solution. Generally, avoid doing design work or discussing technical solutions for longer than a few moments at the betting table.

-

Is this the right time?

- Largely shaped by what we have been doing lately:

- Too long since we released a new feature?

- Too many features released recently that need fixing up?

- Same team has been working on the same thing for a while now? Their morale may dip.

- Might pass on a project because of these

- Largely shaped by what we have been doing lately:

-

Are the right people available?

- Select from a pool of core "product team" when planning teams for each cycle.

- Team depends on expertise required

- This other one is going to invite a lot of scope creep so we need someone who’s good with the scope hammer.

- We need some more front-end programming on this one.

- Preference of players to small/large batch in this cycle

- Vacations or sabbaticals

- After the bets are made, someone from the betting table will write a message that tells everyone which projects we’re betting on for the next cycle and who will be working on them.

- Team should never lose sight of the bigger picture. So don't cut the work into pieces and hand out each item

- Trust the team to take on the entire project and work within the boundaries of the pitch.

- They will have full autonomy and use their judgement to execute the pitch as best as they can.

- Remember: we aren’t giving the teams absolute freedom to invent a solution from scratch. We’ve done the shaping. We’ve set the boundaries. Now we are going to trust the team to fill in the details

- At the end of the cycle, the team will deploy their work. Small teams will make multiple deployments

- Any testing and QA needs to happen within the cycle.

- Help documentation, marketing updates, or announcements are thin-tailed from a risk perspective (they never take 5x as long as we think they will) and are mostly handled by other teams. It doesnt fit in the cycle

- Take care of those updates and publish an announcements during cool-down after the cycle.

- Post the shaped concept to the team

- Team for that project start a kick off call

- The call gives the team a chance to ask any important questions that aren’t clear from the write-up.

- Then, with a rough understanding of the project, they’re ready to get started.

- No deliverables or tasks checked off in the first few days

- Everyone is busy learning the lay of the land and getting oriented.

- Teams have to acquaint themselves with the relevant code, think through the pitch, and go down some short dead ends to find a starting point.

- Empower the team to explictly say “I’m still figuring out how to start” so they don’t have to hide this legitimate work.

- If the silence doesn’t start to break after three days, that’s a reasonable time to step in and see what’s going on.

- As teams get their hands dirty, they discover all kinds of other things that we didn’t know in advance.

- For example, the designer adds a new button on the desktop interface but then notices there’s no obvious place for it on the mobile webview version.

- The way to really figure out what needs to be done is to start doing real work.

- They need to pick something meaningful to build first.

-

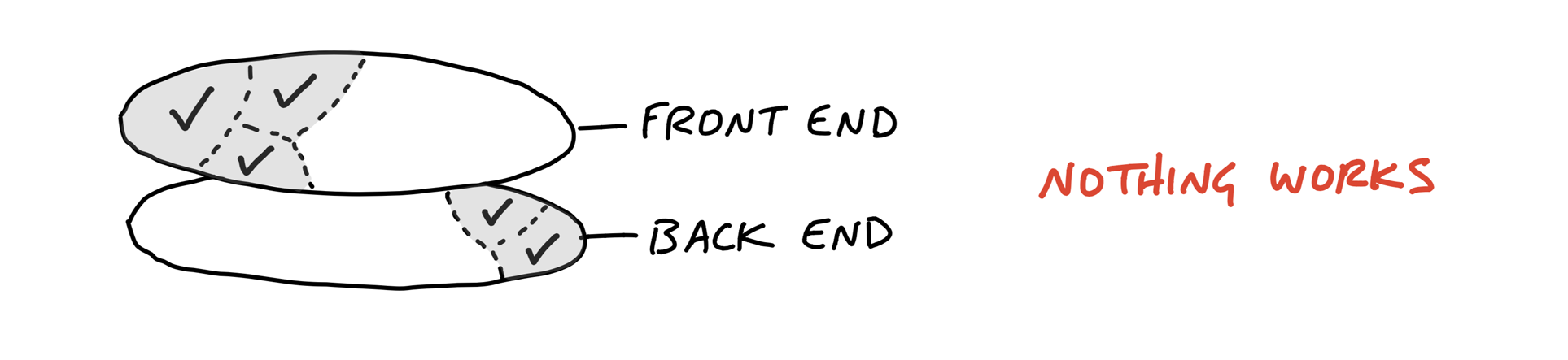

It’s important at the early phase the team doesn't create a master plan of parts that only come together at the 11th hour.

-

A team can do a lot of work but feel insecure because they don’t have anything real to show for it yet.

-

Lots of things are done but nothing is finished.

-

Aim to make something tangible and demoable early—in the first week. This requires integrating vertically on one small piece of the project.

-

Then when one piece is done, the team has something tangible that they’ve proven to work (or not work and reconsider).

-

Case study: Share item with client