In this project for the Udacity Self-Driving Car Nanodegree a deep CNN is developed that can steer a car in a simulator provided by Udacity. The CNN drives the car autonomously around a track. The network is trained on images from a video stream that was recorded while a human was steering the car. The CNN thus clones the human driving behavior.

The goals / steps of this project are the following:

- Use the simulator to collect data of good driving behavior

- Build, a convolution neural network in Keras that predicts steering angles from images

- Train and validate the model with a training and validation set

- Test that the model successfully drives around track one without leaving the road

- Summarize the results with a written report

Please see the rubric points for this project.

The project includes the following files:

- model.py containing the script to create and train the model

- drive.py for driving the car in autonomous mode

- model.h5 containing a trained convolution neural network

- this README.md, this article and image_transformation_pipeline.ipynb for explanation.

Additionally you need to download and unpack the Udacity self-driving car simulator (Version 1 was used). To run the code start the simulator in autonomous mode, open another shell and type

python drive.py model.h5

To train the model, first make a directory ./data/mydata, drive the car in training mode around the track and save the data to this directory. The model is then trained by typing

python model.py

The rest of this README.md provides details about the model used.

The simulated car is equipped with three cameras, one to the left, one in the center and one to the right of the driver that provide images from these different view points. The training track has sharp corners, exits, entries, bridges, partially missing lane lines and changing light conditions. An additional test track exists with changing elevations, even sharper turns and bumps. It is thus crucial that the CNN does not merely memorize the first track, but generalizes to unseen data in order to perform well on the test track. The model developed here was trained exclusively on the training track and completes the test track.

The main problem lies in the skew and bias of the data set. Shown below is a histogram of the steering angles recorded while driving in the middle of the road for a few laps. This is also the data used for training. The left-right skew is less problematic and can be eliminated by flipping images and steering angles simultaneously. However, even after balancing left and right angles most of the time the steering angle during normal driving is small or zero and thus introduces a bias towards driving straight. The most important events however are those when the car needs to turn sharply.

Without accounting for this bias towards zero, the car leaves the track quickly. One way to counteract this problem is to purposely let the car drift towards the side of the road and to start recovery in the very last moment. However, the correct large steering angles are not easy to generate this way, because even then most of the time the car drives straight, with the exception of the short moment when the driver avoids a crash or the car going off the road.

CNNs architectures have been successfully used to predict the steering angle of the simulator. Among these are the CNN architecture of NVIDIA or the comma.ai architecture which were used successfully, e.g. this submission. In this article Vivek Yadav provided a solution to this steering problem based on the judicious use of data augmentation. This submission draws on the insights obtained there but differs in the network architecture and augmentation techniques.

In all of the above architectures a single variable -- the current steering angle -- is predicted as a real valued number. The problem is thus not a classification but a regression task. We will build a similar architecture that predicts a single real valued number, but it would be interesting to see how a discretized version performs.

For the network architecture we draw on a CNN that evolved from a previous submission for classfying traffic signs with high (97.8%) accuracy. However, we included some crucial changes.

The network starts with a preprocessing layer that takes in images of shape 64x64x3. Each image gets normalized to the range [-1,1] otherwise no preprocessing is performed. Following the input layer are 4 convolutional layers. ReLU activations are used throughout the whole network. The first two convolutional layers employ kernels of size k=(8,8) with a stride of s=(4,4) and 32 and 64 channels, respectively. The next convolutional layer uses k=(4,4) kernels, a stride of s=(2,2) and 128 channels. In the last convolutional layer we use k=(2,2), a stride s=(1,1) and again 128 channels. Following the convolutional layers are two fully connected layers with ReLU activations as well as dropout regularization right before the layers. The final layer is a single neuron that provides the predicted steering angle. We explicitly avoided the use of pooling layers because pooling layers apart from down sampling also provide (some) shift invariance, which is desirable for classification tasks, but is counterproductive for keeping a car centered on the road (note: the comma.ai architecture does not use pooling either).

| Layer (type) | Output Shape | Param # | Connected to |

|---|---|---|---|

| lambda_1 (Lambda) | (None, 64, 64, 3) | 0 | lambda_input_1[0][0] |

| convolution2d_1 (Convolution2D) | (None, 16, 16, 32) | 6176 | lambda_1[0][0] |

| activation_1 (Activation) | (None, 16, 16, 32) | 0 | convolution2d_1[0][0] |

| convolution2d_2 (Convolution2D) | (None, 4, 4, 64) | 131136 | activation_1[0][0] |

| relu2 (Activation) | (None, 4, 4, 64) | 0 | convolution2d_2[0][0] |

| convolution2d_3 (Convolution2D) | (None, 2, 2, 128) | 131200 | relu2[0][0] |

| activation_2 (Activation) | (None, 2, 2, 128) | 0 | convolution2d_3[0][0] |

| convolution2d_4 (Convolution2D) | (None, 2, 2, 128) | 65664 | activation_2[0][0] |

| activation_3 (Activation) | (None, 2, 2, 128) | 0 | convolution2d_4[0][0] |

| flatten_1 (Flatten) | (None, 512) | 0 | activation_3[0][0] |

| dropout_1 (Dropout) | (None, 512) | 0 | flatten_1[0][0] |

| dense_1 (Dense) | (None, 128) | 65664 | dropout_1[0][0] |

| activation_4 (Activation) | (None, 128) | 0 | dense_1[0][0] |

| dropout_2 (Dropout) | (None, 128) | 0 | activation_4[0][0] |

| dense_2 (Dense) | (None, 128) | 16512 | dropout_2[0][0] |

| dense_3 (Dense) | (None, 1) | 129 | dense_2[0][0] |

| Total params: 416481 |

All computations were run on an Ubuntu 16.04 system with an Intel i7 processor and an NVIDIA GTX 1080.

Due to the problems with generating the important recovery events manually we decided on an augmentation strategy. The raw training data was gathered by driving the car as smoothly as possible right in the middle of the road for 3-4 laps in one direction. We simulated recovery events by transforming (shifts, shears, crops, brightness, flips) the recorded images using library functions from OpenCV with corresponding steering angle changes. The final training images are then generated in batches of 200 on the fly with 20000 images per epoch. A python generator creates new training batches by applying the aforementioned transformations with accordingly corrected steering angles. The operations performed are

- A random training example is chosen

- The camera (left,right,center) is chosen randomly

- Random shear: the image is sheared horizontally to simulate a bending road

- Random crop: we randomly crop a frame out of the image to simulate the car being offset from the middle of the road (also downsampling the image to 64x64x3 is done in this step)

- Random flip: to make sure left and right turns occur just as frequently

- Random brightness: to simulate differnt lighting conditions

In steps 1-4 the steering angle is adjusted to account for the change of the image. The chaining of these operations leads to a practically infinite number of different training examples.

The steering angle changes corresponding to each of the above operations was determined manually by investigating the result of each transformation and using trigonometry. For example the angle correction corresponding to a horizontal shearing transformation should be proportional to shearing angle.

For validation purposes 10% of the training data (about 1000 images) was held back. Only the center camera imags are used for validation. After few epochs (~10) the validation and training loss settle. The validation loss is consistently about half of the training loss, which indicates underfitting, however with the caveat that training and validation data are not drawn from the same sample: there is no data augmentation for the validation data. A more robust albeit non-automatic metric consists of checking the performance of the network by letting it drive the car on the second track which was not used in training.

We used an Adam optimizer for training. All training was performed at the fastest graphics setting.

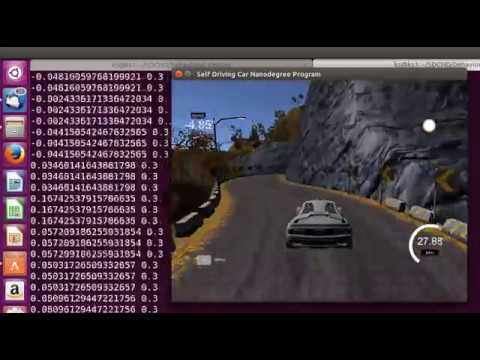

Surprisingly, the car went around the training track almost immediately after introducing the generator. However, it was not reactive enough to complete the test track. Tuning the parameters of the angle correction in the augmentation section of teh code and retraining the network for about 10 epochs fixed the issue and the car mastered the test track. A video of the test track performance is shown here.

The performance of the same CNN on the training track is shown below.

Note that the car successfully recovers from critical situations, even though no recovery events were recorded. All recovery events were generated synthetically by distorting the images of the car driving in the middle of the road, as described above.

By making consequent use of image augmentation with according steering angle updates we could train a neural network to recover the car from extreme events, like suddenly appearing curves change of lighting conditions by exclusively simulating such events from regular driving data.